The Moses of Michelangelo [1] .

I’ll start by saying that I’m not an art connoisseur, but a layman. I have often noticed that the content of a work of art attracts me more than its formal and technical properties, which are what the artist attaches most importance to. I really don’t have the right understanding for many of the means and effects of art. I must say this to ensure a lenient judgment of my attempt.

But works of art have a strong effect on me, especially poetry and plastic works, less often paintings. I have thus been led to tarry long before them on the appropriate occasions and wished to grasp them in my own way, i. H. make me understand how they work. Where I can’t, e.g. B. in music, I am almost incapable of enjoyment. A rationalistic or perhaps analytical disposition in me resists being moved without knowing why I am and what is moving me.

In doing so, I became aware of the apparently paradoxical fact that some of the greatest and most overwhelming creations of art have remained obscure to our understanding. One admires them, one feels conquered by them, but one cannot say what they represent. I am not well-read enough to know whether this has already been noticed, or whether an esthetician has not found that such helplessness of our understanding mind is actually a necessary condition for the highest effects that a work of art is to produce. I could hardly bring myself to believe in this condition.

Not that the art connoisseurs or enthusiasts find no words when they praise such a work of art. You have enough of them, I should think. But in front of such a masterly creation of the artist, as a rule, everyone says something different and no one says what solves the riddle for the simple admirer. In my opinion, what grips us so powerfully can only be the intention of the artist, insofar as he has succeeded in expressing it in the work and allowing us to grasp it. I know that it cannot be a question of merely understanding; it should reflect the emotional state, the psychic constellation which gave the artist the driving force to create, 16be evoked in us again. But why shouldn’t the artist’s intention be specifiable and verbal like any other fact of psychic life? Perhaps this will not succeed in the case of great works of art without the application of analysis. The work itself must make this analysis possible if it is the effective expression of the artist’s intentions and impulses. And in order to guess this intention, I must first find out the meaning and content of what is represented in the work of art, i.e. interpret itbe able. It is therefore possible that such a work of art requires interpretation, and that I can only find out after it has been completed why I have been subject to such a powerful impression. I myself cherish the hope that this impression will not be weakened once we have succeeded in such an analysis.

Now think of Hamlet , Shakespeare’s masterpiece, over three hundred years old [2]. I follow the psychoanalytic literature and agree with the assertion that it was psychoanalysis that first solved the riddle of the effect of this tragedy by tracing the material back to the Oedipus theme. But before that, what an abundance of different, mutually incompatible attempts at interpretation, what a selection of opinions about the character of the hero and the intentions of the poet! Has Shakespeare enlisted our participation for a sick man, or an inadequate inferior, or an idealist only too good for the real world? And how many of these interpretations leave us so cold that they can do nothing to explain the effect of poetry, and instead suggest basing its magic solely on the impression of thought and the splendor of language! And yet,

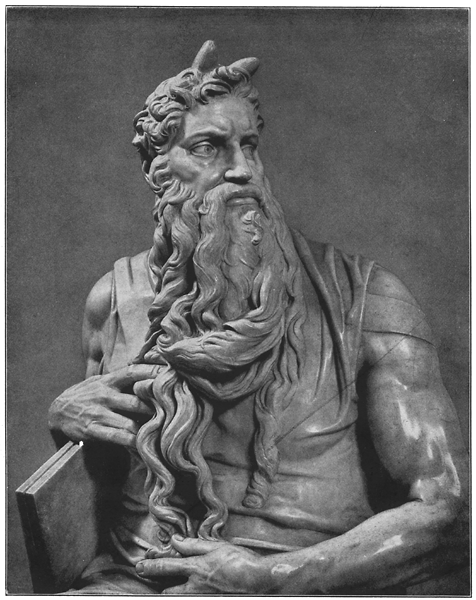

Another of these enigmatic and magnificent works of art is the marble statue of Moses, set up by Michelangelo in the church of S. Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, which is known to be only a part of that huge funerary monument which the artist was to erect for the mighty Pope Julius II [3 ] . I’m always happy when I read a statement about this figure like: she is “the crown of modern sculpture” (Herman Grimm ). For I have never experienced a stronger effect from any picture. How often have I climbed the steep stairs from the ugly Corso Cavour to the lonely square where the abandoned church stands, always trying to withstand the contemptuous, angry look of the hero, and then sometimes I was cautious 17crept out of the semi-darkness of the interior, as if I myself belonged to the rabble on which his eyes are fixed, who cannot hold on to any conviction, who do not want to wait and do not trust, and rejoice when they have regained the illusion of the idol.

With the permission of Verlag Robert Langewiesche from the volume »Michelangelo« of the »Blue Books« collection

With the permission of Verlag Robert Langewiesche from the volume »Michelangelo« of the »Blue Books« collection

But why do I call this statue enigmatic? There is not the slightest doubt that it represents Moses, the lawgiver of the Jews, holding the tablets of the holy commandments. That much is certain, but nothing beyond that. Very recently (1912) an art writer (Max Sauerlandt) can make the statement: »No work of art in the world has been judged in such a contradictory way as this pan-headed Moses. Even the simple interpretation of the figure moves in complete contradiction …’ Using a compilation that dates back only five years, I will explain what doubts are attached to the interpretation of the figure of Moses, and it will not be difficult to show that what is essential and best for understanding this work of art lies concealed behind them [4] .

1.

Michelangelo’s Moses is shown seated, the torso forward, the head with the mighty beard and the gaze turned to the left, the right foot resting on the ground, the left raised so that only the toes touch the ground, the right arm in relation to the tablets and part of the beard; the left arm is laid in the lap. If I wanted to give a more precise description, I would have to anticipate what I have to say later. The authors’ descriptions are sometimes oddly inaccurate. What was not understood was also imprecisely perceived or reproduced. H. Grimm says that the right hand, “under whose arms the tablets of the law rest, grasps the beard.” Likewise W. Lübke: “Shaken, he grabs his right hand into the wonderfully flowing beard …”; Springer : “One (left) hand presses Moses against his body, with the other he unconsciously grabs his mighty flowing beard.” C. Justi finds that the fingers of the (right) hand play with the beard, “like that civilized man in the fuss with the watch chain«. Müntz also emphasizes playing with the beard . H. Thode speaks of the “quiet, firm position of the right hand on the pried open panels.” Even in the right hand he does not recognize a game of excitement, like Justi and similar Boitowant. »The hand remains as it was held, gripping the beard, before the Titan turned his head to the side.« Jakob Burkhardt explains, »that the famous left arm in the18 basically have nothing else to do than hug that beard to my body.”

If the descriptions do not agree, we will not be surprised at the difference in perception of individual features of the statue. I don’t think we can characterize Moses’ expression any better than Thode , who read it as a “mixture of anger, pain and contempt, the anger in the menacingly furrowed eyebrows, the pain in the eyes, the contempt in the protruding lower lip and the downturned corners of the mouth. But other admirers must have seen things differently. So Dupaty had judged: Ce front auguste semble n’être qu’un voile transparent, qui couvre à peine un esprit immense [5] . On the other hand, says Lübke: »One would look in vain for the expression of higher intelligence in the head; nothing but the capacity for tremendous anger, for an all-encompassing energy, is expressed in the crowded forehead.« Guillaume (1875) goes even further in the interpretation of the facial expression, who found no excitement in it, »only proud simplicity, soulful dignity, energy of faith. Moses looks to the future, he foresees the permanence of his race, the immutability of his law”. Similarly, Müntz lets ‘Moses’ eyes wander far beyond the human race; they are aimed at the mysteries which he was the only one to keep”. Yes, for Steinmannis this Moses “no longer the rigid legislator, no longer the terrible enemy of sin with the anger of Jehovah, but the royal priest, whom old age must not touch, who blesses and prophesies, the reflection of eternity on his forehead, of his people takes his final farewell«.

There have been others to whom Michelangelo’s Moses said nothing at all, and who were honest enough to say so. As one reviewer in the Quarterly Review 1858 put it : ‘ There is an absence of meaning in the general conception, which precludes the idea of a self-sufficing whole … « And one is amazed to learn that others found nothing to admire about Moses, but rebelled against him, accusing the brutality of the figure and the animal-likeness of the head.

Did the Master really write such indistinct or ambiguous writing in the stone that such varied readings were possible?

But another question arises, to which the uncertainties mentioned are easily subordinated. Did Michelangelo want to create a “timeless character and mood picture” in this Moses, or did he depict the hero at a specific, but highly significant moment in his life? A plural19 of judges opts for the latter and also knows how to indicate the scene from the life of Moses, which the artist has captured for eternity. It is the descent from Sinai, where he received the Tablets of the Law from God, and the perception that the Jews have meanwhile made a golden calf, which they dance about with joy. His gaze is directed at this picture, this sight evokes the feelings that are expressed in his countenance and will immediately set the mighty figure into violent action. Michelangelo chose the moment of the last hesitation, the calm before the storm, for the depiction; next Moses will jump up – left foot off the ground – smash the tablets to the ground and unleash his wrath on the apostates.

Their representatives also differ in details of this interpretation.

yak Burkhardt : »Moses seems to be depicted at the moment when he sees the worship of the golden calf and wants to jump up. It lives in its form the preparation for a mighty movement, such as one can only tremble expect from the physical power with which it is endowed.«

W. Lübke : »Assow he flashing eyes just the outrage of the worship of the golden calf, so violently an inner movement shoots through the whole figure. Shaken, he grabs his wonderfully flowing beard with his right hand, as if he wants to keep his movements under control for a moment and then drive off all the more crushingly.«

Springer agrees with this view, not without raising a concern that will continue to claim our attention: »Burning with strength and zeal, the hero only laboriously fights down his inner excitement …… One therefore involuntarily thinks of a dramatic scene and thinks that Moses is depicted at the moment when he sees the worship of the golden calf and is about to jump up in anger. This assumption hardly reflects the true intention of the artist, since Moses, like the other five seated statues of the superstructure [6] , was supposed to have a predominantly decorative effect; but it can be regarded as a brilliant testimony to the fullness of life and the personal nature of the figure of Moses.«

Some authors, who do not exactly choose the scene of the golden calf, agree with this interpretation in the most essential point, that this Moses is about to jump up and go into action.

Herman Grimm : »(This figure) fills you with majesty, a self-confidence, a feeling as if the thunder suits this man20 heaven’s commandments, but he restrained himself before unleashing them, waiting to see if the enemies he would destroy dared to attack him. He sits there as if about to jump up, his head proudly raised from his shoulders, with his hand under whose arms the Tablets of the Law rest, grasping his beard, which falls in heavy streams on his chest, with his nostrils breathing widely and with a mouth on whose lips words seem to tremble.”

Heath Wilson says Moses’s attention was caught by something, he was about to jump up but hesitated. The look, in which indignation and contempt are mixed, could change to pity.

Wölfflin speaks of “inhibited movement”. The reason for the inhibition lies in the will of the person himself; it is the last moment of self-restraint before breaking free, i. H. before jumping up.

C. Justi based the interpretation most thoroughly on the perception of the golden calf and linked otherwise unnoticed details of the statue to this view. He draws our attention to the indeed conspicuous position of the two tablets of the law, which are about to slide down onto the stone seat: “So he (Moses) could either be looking in the direction of the noise with an expression of foreboding, or it would be the sight of the abomination itself, which hits him like a deafening blow. Trembling with disgust and pain he has settled down [7]. He had stayed on the mountain for forty days and nights, so he was tired. The monstrous, a great destiny, crime, even happiness can be perceived in a moment, but cannot be grasped in terms of its essence, depth, consequences. For a moment his work seems destroyed, he despairs of this people. At such moments the inner turmoil reveals itself in involuntary small movements. He lets the two tablets he is holding in his right hand slide down onto the stone seat, they have come to stand at an angle, pressed by his forearm to the side of his chest. But the hand goes to the breast and beard, when turning the neck to the right it has to pull the beard to the left side and break the symmetry of this broad masculine adornment; it looks like the fingers are playing with the beard, like the civilized man in the excitement with the watch chain. The left one digs into the skirt on the belly (in the Old Testament the bowels are the seat of the affects). But the left leg is already drawn back and the right one advanced; in the next moment it will spring up, the psychic force from the sensation to the21 Jump over the will, move your right arm, the tablets will fall to the ground and rivers of blood will atone for the shame of the apostasy….” “It’s not yet the moment of tension of the deed. The mental pain still reigns almost paralyzing.«

Fritz Knapp expresses himself in a similar way ; only that he removes the situation at the beginning from the previously expressed concerns, and also continues the indicated movement of the panels more consistently: ‘He, who was just alone with his god, is distracted by earthly noises. He hears noise, the shouting of sung dance dances wakes him from the dream. The eye, the head turn to the sound. Fright, anger, the whole fury of wild passions run through the giant figure at the moment. The Tablets of the Law begin to slide down, they will fall to the ground and shatter as the figure rises up to hurl the thunderous words of wrath into the masses of the apostate people…. This moment of greatest tension is chosen….’ Closethus emphasizes the preparation for the action and disputes the representation of the initial inhibition as a result of the overwhelming excitement.

We will not deny that there is something immensely appealing about attempts at interpretation such as the last-mentioned by Justi and Knapp . They owe this effect to the fact that they do not stop at the overall impression of the figure, but appreciate individual characters of it, which one otherwise overwhelms and, as it were, paralyzed, fails to notice. The decisive turning of the head and eyes of the figure, who is otherwise facing forward, gives good reason to believe that something is being seen there that suddenly draws the resting person’s attention. The foot lifted off the ground hardly allows any other interpretation than that of a preparation to jump up [8], and the very strange posture of the panels, which are something highly sacred and are not allowed to be housed in the room like any other attribute, is explained well by the assumption that the excitement of their wearer caused them to slide down and then they would fall to the ground. So we would know that this statue of Moses represents a certain significant moment in the man’s life, and we would not be in danger of mistaking that moment.

Just two remarks from Thode snatch from us what we thought we already had. This observer says he does not see the tablets sliding down, but “standing still.” He notes “the calm, firm posture of the right hand on the pried open panels.” If we take a look for ourselves, we must unreservedly agree with Thode . The panels are fixed and not in danger of sliding. The right hand supports or leans on them.22 This does not explain how they are set up, but it makes it unusable for the interpretation of Justi and others.

A second remark is even more crucial. Thode warns that ‘this statue was intended as one of six and is shown seated. Both contradict the assumption that Michelangelo wanted to fix a specific historical moment. For, as far as the first is concerned, the task of presenting figures seated side by side as types of human nature ( vita activa! vita contemplativa! ) precludes the representation of individual historical events. And with regard to the second, the representation of the sitting, which was conditioned by the entire artistic conception of the monument, contradicts the character of that event, namely the descent from Mount Sinai to the camp.

Let us adopt Thode ‘s scruples; I think we’ll be able to increase its power even further. Moses was to adorn the plinth of the tomb monument with five (three in a later draft) other statues. His closest match should have been a Paulus. Two of the others, the vita activa and contemplativawere executed as Lea and Rahel on the pitifully stunted monument that exists today, albeit standing. The fact that Moses belongs to an ensemble makes it impossible to assume that the figure should arouse the expectation in the viewer that it will immediately jump up from its seat, perhaps storm off and make a noise of its own accord. If the other figures were not also depicted in preparation for such violent action, which is very improbable, it would make the worst impression if just one could give us the illusion that she was about to leave her place and her comrades , i.e. to evade their task in the structure of the monument. That would result in a gross incoherence that one should not expect of the great artist without the utmost compulsion.

So this Moses must not want to jump up, he must be able to remain calm, like the other figures, like the intended image (not executed by Michelangelo) of the Pope himself. But then the Moses we are looking at cannot represent the a man in a rage coming down from Sinai, finding his people apostate and throwing down the holy tablets to shatter them. And indeed, I remember my disappointment when, on previous visits to S. Pietro in Vincoli, I sat down in front of the statue, expecting that I would now see it spring up on its raised foot, like the panels hurl to the ground and unleash their wrath. None of this happened; instead he became23 The stone became more and more rigid, an almost oppressive holy stillness emanated from it, and I had to feel that something was being represented here that could remain the same, this Moses would sit there forever and be angry like this.

But if we have to give up the interpretation of the statue with the moment before the outbreak of anger at the sight of the idol, we have little choice but to accept one of the views which want to see a character image in this Moses. Thode ‘s judgment appears to be the most free from arbitrariness and best based on the analysis of the figure’s movement motives: »Here, as always, he is concerned with the formation of a character type. He creates the image of a passionate leader of mankind, aware of his divine legislative task, who meets the foolish opposition of men. There was no other means of characterizing such a man of action than to show the energy of the will, and this was possible through the illustration of a movement penetrating the apparent stillness, as exemplified in the turning of the head, the tensing of the muscles, the Position of the left leg expresses itself. These are the same phenomena as with the vir activusthe Medici chapel Giuliano. This general characteristic is further deepened by emphasizing the conflict in which such a genius who shapes humanity enters into the generality: the affects of anger, contempt, and pain attain typical expression. Without this, the essence of such a superman could not be made clear. Not a historical picture, but a character type of insurmountable energy, which tames the resisting world, was created by Michelangelo, shaping the traits given in the Bible, his own inner experiences, impressions of Julius’ personality and, I believe, also those of Savonarola’s fighting activity.«

One can place Knackfuss ‘s remarks in the vicinity of these statements : The main secret of the effect of Moses lies in the artistic contrast between the inner fire and the external calm of the attitude.

I don’t find anything in me that would resist Thode ‘s explanation , but I miss something. Perhaps there is a need for a more intimate relationship between the hero’s state of mind and the contrast between “apparent calm” and “inner agitation” expressed in his attitude.

2.

Long before I could hear anything about psychoanalysis, I learned that a Russian art connoisseur, Ivan Lermolieff , whose first essays were published in German in 1874-76, was causing a revolution in the galleries of Europe24 by revising the allocation of many pictures to the individual painters, by teaching them to distinguish copies from originals with certainty, and by constructing new artist individualities from works that had become free of their earlier designations. He accomplished this by discarding the general impression and broad outlines of a painting, and emphasizing the distinctive importance of minor details, such trifles as the formation of the fingernails, the ear-lobes, the halo, and other unnoticed things which the copyist should imitate neglected, and which every artist carries out in a way that is characteristic of him. I was then very interested to learn that an Italian doctor named Morelli was behind the Russian pseudonym, had hidden. He died in 1891 as Senator of the Kingdom of Italy. I believe his procedure is closely related to the technique of medical psychoanalysis. This, too, is accustomed to guessing the secret and the hidden from underestimated or unnoticed features, from the rubbish – the “ refuse ” – of observation.

In two places in the figure of Moses there are details that have not been taken into account before, and that have actually not yet been properly described. They concern the position of the right hand and the position of the two panels. One may say that this hand mediates in a very peculiar, forced way, demanding explanation, between the panels and the beard of the angry hero. It has been said that she rummaged in her beard with her fingers, playing with the strands of it, while leaning on the tablets with the edge of her little finger. But this is apparently not the case. It is worth considering more carefully what the fingers of this right hand do, and to describe in detail the powerful beard to which they relate [9] .

One then sees with all clarity: The thumb of this hand is hidden, the index finger and this alone is in effective contact with the beard. He presses himself so deeply into the soft masses of hair that they swell above and below him (headward and bellyward of the pressing finger) above his level. The other three fingers, bent at the small joints, brace themselves against the chest wall; they are just brushed by the rightmost braid of the beard, which overhangs them. They have, so to speak, eluded the beard. So one cannot say that the right hand is playing with the beard or rummaging in it; nothing else is correct than that one index finger is placed over part of the beard and makes a deep groove in it. press his beard with a finger,

The much admired beard of Moses runs from cheeks,25 Upper lip and chin down in a number of strands which can still be distinguished in their course. One of the extreme right hair strands which emanates from the cheek, runs to the upper edge of the weighting index finger, which stops it. We can assume it slides further down between this and the covered thumb. The strand on the left that corresponds to it flows nearly without distraction down to the chest. The thick mass of hair inward from this latter strand, reaching from it to the midline, has met the most conspicuous fate. She cannot follow the turn of the head to the left, she is forced to form a gently rolling arch, a piece of a garland, crossing the inner masses of hair on the right. It is held in place by the pressure of the right index finger, although it originated to the left of the center line and actually represents the main part of the left half of the beard. The bulk of the beard thus appears thrown to the right, although the head is turned sharply to the left. At the point where the right forefinger presses in, something like a whorl of hair has formed; strands from the left lie above strands from the right, both compressed by the violent finger. Only beyond this point do the masses of hair, which have been diverted from their direction, break free and now run down vertically until their ends are picked up by the open left hand resting in the lap.

I do not delude myself about the insightfulness of my description and do not dare to judge whether the artist really made it easy for us to undo that knot in the beard. But beyond this doubt the fact remains that the pressure of the index finger of the right hand was mainly on strands of hair from the lefthalf of the beard is concerned, and that this encroaching influence keeps the beard from following the turning of the head and looking to the left. One may now ask what this arrangement is supposed to mean and to what motives it owes its existence. If it was really considerations of line management and filling of space that induced the artist to stroke the flowing mass of beard of Moses, who is looking to the left, across to the right, how strangely unsuitable does the pressure of a finger appear as a means for this? And who, having for some reason forced his beard to the other side, would then think of fixing one half of the beard on top of the other by the pressure of a finger? But maybe these basically minor moves don’t mean anything and we worry about things

Let us proceed on the premise that these details, too, have meaning. There is then a solution that removes the difficulties and lets us glimpse a new meaning. When26 in the figure of Moses the strands of beard on the left lie under the pressure of the right index finger, this can perhaps be understood as the remainder of a relationship between the right hand and the left half of the beard, which in a moment earlier than the one represented was a far more intimate one. The right hand had perhaps grasped the beard far more vigorously, had reached the left edge of it, and when it withdrew into the posture which we now see on the statue, part of the beard followed and now bears witness to the Movement that has expired here. The beard garland would be the trace of the path traversed by this hand.

So that’s how we tapped into a right-hand backward movement. One assumption imposes others on us as if inevitable. Our imagination completes the process of which the movement attested by the trace of the beard is a part, and leads us, without constraint, to the conception of the resting Moses being startled by the noise of the people and the sight of the golden calf. He sat quietly, head forward with the flowing beard, the hand probably had nothing to do with the beard. Then the noise hits his ear, he turns his head and looks in the direction from which the disturbance is coming, sees the scene and understands it. Now he is gripped by anger and indignation, he wants to jump up, punish the wicked, destroy them. The rage that knows it is still far from its object meanwhile directed as a gesture against one’s own body. The hand, impatient and ready for action, reaches forward into the beard which had followed the turn of the head, presses it with an iron grip between thumb and palm with the fingers closing, a gesture of a force and ferocity reminiscent of other representations of Michelangelo like. But then, we don’t yet know how and why, a change occurs, the outstretched hand that has been sunk into the beard is hastily withdrawn, its grip releases the beard, the fingers separate from it, but they were so deeply dug into it , that in their retreat they draw a mighty strand from the left side to the right, where it must, under the pressure of the one, longest and uppermost finger, overlay the braids of the right beard. And this new position

It’s time to reflect. We have assumed that the right hand was first outside the beard, then, in a moment of high emotional tension, it reached over to the left to grasp the beard, and finally drew back, taking part of the beard with it. We switched with this right hand as if we were free to dispose of it. But are we allowed to do this? Is that hand free? If she does not have to hold or carry the sacred tablets, then such mimics are her27 Excursions not prohibited by your important task? And further, what should cause it to move back if it had followed a strong motive to get out of its initial position?

These are really new difficulties. However, the right hand belongs to the panels. Nor can we deny here that we lack a motive which could induce the right hand to retreat. But how would it be if both difficulties could be solved together and only then resulted in a process that could be understood without a gap? What if something happening on the blackboards enlightened us about the movements of the hand?

There is something to be noted about these tablets which has hitherto not been found worth observing [10].. It was said: the hand leans on the tablets or: the hand supports the tablets. One can also easily see the two rectangular panels placed next to each other standing on the edge. If one looks more closely, one finds that the lower edge of the panels is formed differently from the upper edge, which is inclined forwards. This upper one is limited in a straight line, but the lower part shows a projection like a horn in its front part, and it is with this projection that the tablets touch the stone seat. What can be the meaning of this detail, which, by the way, is reproduced quite incorrectly in a large plaster cast in the collection of the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts? There is little doubt that this horn is supposed to mark the upper edge of the tablets according to the writing. Only the upper edge of such rectangular tablets tends to be rounded or flared. So the panels are upside down here. Now this is a strange treatment of such sacred objects. They are turned upside down and almost balanced on a point. Which formal element can contribute to this design? Or is this detail supposed to have been irrelevant to the artist?

The idea arises that the panels also came into this position as a result of a movement that had taken place, that this movement was dependent on the inferred change of location of the right hand, and that it then in turn forced this hand to move back later. The actions in the hand and those on the tablets combine to form the following unit: Initially, when the figure was sitting still, he carried the tablets upright under his right arm. The right hand grasped the lower edges, finding support on the forward projection. This ease of carrying easily explains why the panels were held upside down. Then came the moment when the silence was disturbed by the noise. Moses turned his head, and when he had seen the scene,30 Bart, as if to exercise her impetuosity on her own body. The tablets were now entrusted to the pressure of the arm, intended to press them against the chest wall. But this fixation was not enough, they began to slide forwards and downwards, the upper rim, previously held horizontally, directed forwards and downwards, the lower rim, deprived of support, approached the stone seat with its front point. A moment further and the panels should have rotated around the newly found base, hitting the ground with the previously upper edge first and smashing against it. To prevent this, withdraws the right hand and releases the beard, part of which is unintentionally dragged along, reaches the edge of the panels and supports them near their rear corner, which has now become the uppermost corner. The ensemble of beard, hand and pair of panels placed on their point, which seems strangely forced, is derived from the one passionate movement of the hand and its well-founded consequences. If one wants to undo the traces of the movement storm that has passed, one must lift the front upper corner of the panels and push them back into the picture plane, so that the front lower corner (with the projection) can be removed from the stone seat, lower your hand and put it under the ones that are now horizontal lower edge of the board.

I had three drawings made by an artist, which should clarify my description. The third of these represents the statue as we see it; the other two represent the preliminary stages that my interpretation postulates, the first that of rest, the second that of the greatest tension, the readiness to jump up, the turning away of the hand from the panels and the beginning of sliding down them. It is now remarkable how the two illustrations supplemented by my draftsman honor the inaccurate descriptions of earlier authors. A contemporary of Michelangelo , Condivi, said: »Moses, the duke and captain of the Hebrews, sits in the position of a musing sage, holding the Tablets of the Law under his right arm and supporting his chin with his left hand (!), like one who is weary and full of worries. « This cannot be seen in the statue of Michelangelo , but it agrees with the assumption on which the first drawing is based. Like other observers, W. Lübke had written: “Shaken, he grips his wonderfully flowing beard with his right hand . ” Justi and Knapphave seen, as mentioned, that the panels are about to slide down and are in danger of breaking. They had to be corrected by Thode that the tablets were securely fixed by the right hand, but they would be right in describing not the statue but our middle stage . One might almost think that these authors had liberated themselves from the facial image of the statue31 and would have unwittingly begun an analysis of their motives for movement, by which they were led to the same requirements as we have more consciously and explicitly set out.

3.

If I am not mistaken, we shall now be permitted to reap the fruits of our toil. We have heard how many, impressed by the statue, have been led to believe that it represents Moses under the influence of the sight of his people having fallen away and dancing about an idol. But this interpretation had to be abandoned, for it continued with the expectation that he would jump up in a moment, smash the tablets and carry out the work of revenge. However, this contradicted the determination of the statue as part of the grave monument of Julius II alongside three or five other seated figures. We may now take up this abandoned interpretation again, for our Moses will not jump up and will not hurl the tablets away. what we see in him is not the introduction to a violent action, but the remainder of a completed movement: he wanted to do it in a fit of anger, jump up, take revenge, forget about the blackboards, but he has overcome the temptation, he will now remain seated in a tamed manner Anger, in pain mixed with contempt. Nor will he throw away the tablets so that they shatter on the stone, for it was precisely because of them that he controlled his anger, to save them he mastered his passion. Giving himself over to his passionate indignation, he had to neglect the tablets, withdraw from them the hand that carried them. Then they began to slide down, in danger of breaking. That warned him. He remembered his mission and renounced the gratification of his affect for it. His hand flew back and saved the sinking tablets, before they could fall. He stayed in that position, and so did himMichelangelo depicted as guardian of the tomb.

A triple layering is expressed in his figure in the vertical direction. The emotions that have become dominant are reflected in the expressions of the face, the signs of the suppressed movement are visible in the middle of the figure, the foot still shows the position of the intended action, as if the mastery had progressed from top to bottom. The left arm, which has not yet been mentioned, seems to have its share in our interpretation. His hand is placed in his lap with a soft gesture and embraces the last ends of the falling beard as if caressing. It gives the impression that she wants to undo the violence with which the other hand had abused the beard a moment before.

But now people will object to us: So that’s the way it is32 not the Moses of the Bible, who really got angry and threw down the tablets so that they broke. That would be a very different Moses from the artist’s sensibilities, who would have presumed to emend the sacred text and falsify the character of the divine man. May we expect this freedom from Michelangelo , which is perhaps not far from a sacrilege in the saint?

The scriptural passage in which Moses’ behavior at the scene of the golden calf is recorded is as follows (I beg your pardon for using Luther’s translation in an anachronistic way ):

(II. B. Chap. 32.) »7. But the Lord said to Moses: Go, come down; for your people, which you brought out of Egypt, have destroyed them. 8. They quickly strayed from the way that I commanded them. They made themselves a cast calf and worshiped it and sacrificed to it, saying, These are your gods, Israel, who brought you out of the land of Egypt. 9. And the Lord said to Moses: I see that the people are stiff-necked. 10. And now let me, that my anger be kindled against them, and destroy them; so I will make you a great people. 11 Moses pleaded with the LORD his God, saying, “Lord, why does your anger burn out against your people, whom you brought out of the land of Egypt with great power and a mighty hand?…

… 14. So repented the Lord for the evil which he threatened to do to his people. 15. Moses turned and came down from the mountain, and had in his hand two tablets of testimony, which were written on both sides. 16. And God Himself had made them, and Himself dug the Scriptures into them. 17 When Joshua heard the shouting of the people shouting for joy, he said to Moses, There is shouting in the camp as in battle. 18. He answered: It is not a cry of triumph and defeat against one another, but I hear a cry of a victory dance. 19. But when he came near the camp and saw the calf and the dance, he became angry with rage, and threw the tablets out of his hand, and broke them at the foot of the mountain; 20. And took the calf that they had made, and melted it with fire, and crushed it with powder, and dusted it on the water, and gave it to the children of Israel to drink; …

30. In the morning Moses said to the people: You have committed a great sin; now I will go up to the Lord, if I may perhaps atone for your sins. 31. When Moses came again to the Lord, he said, Alas, the people have committed a great sin, and have made gods of gold for themselves. 32. Now forgive them their sin; if not, blot me out from your book that you have written. 33. The Lord said to Moses: What? I will blot out from my book whoever sins against me. 34. So go now33 and lead the people to where I have told you. Behold, my angel shall go before you. I will well visit their sin when my time comes to visit. 35. So the Lord punished the people because they had made the calf which Aaron had made.”

Under the influence of modern Bible criticism, it becomes impossible for us to read this passage without finding in it the signs of clumsy composition from multiple source accounts. In verse 8 the Lord Himself tells Moses that the people have fallen away and made an idol for themselves. Moses prays for sinners. Yet in verse 18 he behaves against Joshua as if he does not know it, and flares up in sudden anger (verse 19) as he beholds the scene of idolatry. In verse 14 he has already obtained God’s forgiveness for his sinful people, but in verse 31 ff. he goes up the mountain again to beg this forgiveness, reports to the Lord about the apostasy of the people and receives the assurance of a stay of punishment. Verse 35 refers to a punishment of the people by God, of which nothing was told, while in verses 20-30 the judgment that Moses himself carried out was described. It is well known that the historical parts of the book dealing with the Extract are riddled with even more striking incongruities and contradictions.

For the people of the Renaissance there was of course no such critical attitude towards the text of the Bible; they had to interpret the report as a coherent one and then found that it offered no good starting point for the visual arts. The Moses of the passage had already been taught of the people’s idolatry, had sided with clemency and forgiveness, and then suddenly succumbed to a fit of rage when he beheld the golden calf and the dancing crowd. So it would not be surprising if the artist who wanted to depict the hero’s reaction to this painful surprise had made himself independent of the Bible text for inner motives. Nor was such a deviation from the wording of the Holy Scriptures for minor motives by any means unusual or denied to the artist.Parmigiano in his native city shows us Moses sitting on top of a mountain and throwing the tablets to the ground, although the Bible verse expressly says that he broke them at the foot of the mountain. Even the depiction of a seated Moses finds no basis in the Bible text and seems to agree with those judges who assumed that Michelangelo ‘s statue did not intend to capture any specific moment in the life of the hero.

More important than the disloyalty to the sacred text is probably the transformation that, according to our interpretation, Michelangelo undertook with the character of Moses. The man Moses, according to the testimonies of tradition, was irascible and subject to outbursts of passion. In such a fit of holy34 In anger he had killed the Egyptian who was mistreating an Israelite, and therefore had to flee the country into the wilderness. In a similar outburst of emotion, he shattered the two tablets that God Himself had written. When tradition reports such character traits, it is probably unbiased and has retained the impression of a great personality who once lived. But Michelangeloplaced another Moses on the Pope’s tomb monument, which is superior to the historical or traditional Moses. He has reworked the motif of the broken tablets of the law; he does not allow them to be broken by Moses’ anger, but rather calms this anger with the threat that they might break, or at least hinders it on the way to action. In doing so, he has placed something new and superhuman in the figure of Moses, and the mighty body mass and powerful musculature of the figure only becomes a physical means of expression for the highest psychological achievement that is possible for a human being, for overcoming one’s own passion in favor of and on behalf of others a purpose to which one is dedicated.

Here the interpretation of the statue of Michelangelo may come to an end. One can still ask what motives were active in the artist when he chose Moses, and a Moses transformed in this way, for the tomb of Pope Julius II. It was unanimously pointed out from many quarters that these motifs were to be found in the character of the pope and in the artist’s relationship to him. Julius II was Michelangelorelated in that he sought to realize great and mighty things, above all the greatness of dimension. He was a man of action, his aim was definable, he strove for the unification of Italy under the rule of the papacy. What was only to be achieved several centuries later through the cooperation of other powers, he wanted to achieve alone, an individual in the short span of time and rule that was granted to him, impatient with violent means. He knew Michelangeloas his equal, but he often made him suffer because of his short temper and his ruthlessness. The artist was aware of the same intensity of striving and, as a more profound brooding mind, may have sensed the lack of success to which they were both doomed. So he attached his Moses to the Pope’s monument, not without reproaching the deceased, as a warning to himself, rising above his own nature with this criticism.

4.

In 1863 an Englishman W. Watkiss Lloyd dedicated a small book to Moses by Michelangelo [11] . When it35 I managed to get hold of this 46-page document, but I took note of its content with mixed feelings. It was an opportunity to experience first-hand what unworthy infantile motives tend to contribute to our work in the service of a great cause. I regretted that Lloyd had anticipated so much that was valuable to me as a result of my own efforts, and it was only in the second instance that I could rejoice in the unexpected confirmation. At a crucial point, however, we parted ways.

Lloyd was the first to notice that the usual descriptions of the character are incorrect, that Moses is not about to get up [12] , that the right hand is not grasping the beard, that only the index finger is still resting on the beard [13]. He also saw, which means far more, that the depicted pose of the figure can only be clarified by referring back to an earlier, non-depicted moment, and that the pulling over of the left strand of beard to the right is intended to indicate the right hand and the left half of the beard had previously been in an intimate, naturally mediated relationship. But he takes a different route to reestablishing this neighborhood, which has been made accessible by necessity; he doesn’t let his hand in his beard, but rather has his beard at hand. He explains that one has to imagine that “a moment before the sudden disturbance, the head of the statue was turned fully to the right over the hand which then, as now, holds the Tablets of the Law”.wake «) should be understood.

Lloyd allows himself to be held back from the other possibility of an earlier approach of the right hand and the left half of the beard by a consideration which shows how close he missed our interpretation. It was not possible that the Prophet, even in the greatest excitement, could have stretched out his hand to pull his beard aside like that. In that case the position of the fingers would have been quite different, and moreover, as a result of this movement, the tablets, which are held only by the pressure of the right hand, would have had to fall down36 because, in order to preserve the panels, the figure is expected to perform a very clumsy movement, the idea of which actually contains a degradation. (» clutch Unless by a gesture so awkward, that to imagine it is profanation. «)

It is easy to see where the author’s omission lies. He correctly interpreted the peculiarities of the beard as signs of a past movement, but then neglected to apply the same conclusion to the no less constrained details of the placement of the tablets. He uses only the signs from the beard, not also those from the tablets, the position of which he accepts as the original. So he blocked the way to a conception like ours, which, by evaluating certain inconspicuous details, arrived at a surprising interpretation of the whole figure and its intentions.

But what if we were both on the wrong track? What if we were to absorb details with difficulty and meaning, of which the artist was indifferent, which he would have made purely arbitrarily or for certain formal occasions just as they are, without putting anything secret into them? What if we had fallen into the lot of so many interpreters who think they see clearly what the artist neither consciously nor unconsciously wanted to create? I can’t decide about that. I don’t know if it’s up to an artist like Michelangelo, in whose works so much content of thought struggles for expression, to believe such a naive vagueness, and whether this is just acceptable for the striking and strange features of the statue of Moses. Finally, one may timidly add that the artist has to share the blame for this uncertainty with the interpreter. Michelangelo often enough went in his creations to the extreme limit of what art can express; perhaps he was not entirely successful with Moses, either, if it was his intention to have the storm of violent excitement guessed at from the signs that remain after the calm has passed.

Fig.D

Fig.D 1

1 2

2 3

3

You must be logged in to post a comment.